In recognition of COP26, we ask what is the best thing we’ve seen recently for active travel (AT) from the Scottish Government – and what is the biggest challenge they face in the coming year? We have no doubts about the answers!

Certainly, the top Scottish Government AT action this year was the announcement on cash, whilst equally clearly the biggest challenge is adopting policies which will achieve their 20% traffic reduction target.

Scottish Government AT cash

The recent deal between the Scottish Greens and SNP, and its confirmation in the Programme for Government, are truly momentous as regards cash for active travel.

10% of the Transport Budget (or a minimum of £320m) will be allocated to AT by 24/25 – compared to £115m in the current year, 21/22. Currently Scotland and Wales are roughly on a par with each other, at just over £20 per person per year. This is way ahead of England and not far from investment levels in bike-friendly European countries.

However, by 24/25, annual investment in Scotland will be around £60 per person per year – possibly the highest for any country in Europe if not worldwide (some individual cities may be higher – in Scotland or elsewhere). Of course, Scotland is at present infinitely far behind many of its European neighbours in terms of infrastructure, but this investment, if continued beyond the next election, could put us on a path to catching up. Rapid transition from private motor traffic to more travel on foot and by bike, as well as to public and shared transport, is, of course, vital in view of the climate crisis.

Cash questions

One thing we don’t know is how the AT cash increase will be phased over the next 3 budgets. Leaving budgets largely unchanged until 24/25 would be a real failure of ambition, and the sudden massive rise would then be extremely hard for Councils to manage. A good approach would be roughly equal spacing of the increase over the 3 years, which would mean AT cash up from £115m in 21/22 to some £180m in the forthcoming 22/23 budget (the draft budget is expected in December).

A huge challenge will be ensuring the skills, training and political leadership necessary for the rapidly growing AT cash to be fully used and to be effectively used. Transport Scotland, Council officers, transport consultancies and many politicians have for years been geared to a ‘car is king’ mentality. Whilst that has begun to change in some Councils, such as Edinburgh and Glasgow, government must take the lead in ensuring widespread culture change and training right across Scotland.

Finally, big thanks to the organisations and individuals (you?) who, for many years, have pushed politicians for realistic AT investment. This came to a head at the April 2021 Holyrood election where Green, Lab and Con manifestos all promised 10% of the entire transport budget for AT, whilst Lib Dem and SNP promised substantial though much lesser rises. Now, under the Green/SNP deal, the full 10% has been agreed, to be fully in place by the last budget of this Parliament.

Scottish Government Traffic Order improvements

Another excellent development, and one which will make the cash easier to use effectively, is that the government seems to have listened to the many people, the Councils like Edinburgh and Glasgow, and other concerned organisations, who have urged reform of the rules governing Traffic Orders – which have caused unconscionable delays and complexities for AT projects in Edinburgh.

For example, whilst there are many reasons for the dreadful delays in implementing the CCWEL city-centre west-east cycleroute project, literally two years were occupied by the Scottish Government, at considerable expense, looking in forensic detail into relatively minor objections – so minor that all were eventually dismissed. This delay in turn increased costs, which led to further delay to identify cost ‘savings’ – mainly through reducing ‘placemaking’ aspects of the scheme.

In terms of complexities, the disfunctional Traffic Order rules have forced Edinburgh into crazy processes of TTRO (temporary Traffic Regulation Order) followed by ETRO (experimental TRO), to be followed by TRO, with multiple public consultations, in order to make successful Spaces for People projects permanent.

Now, thanks to pressure from individuals (you?), organisations and Councils…

- Objections to certain Traffic Orders (such as those which delayed CCWEL) will only trigger a full government investigation on the basis of their content, not purely on the number of objections

- According to an Edinburgh Transport Committee Paper [para 5.6] the Scottish Government is expected on 26 November to announce changes to Traffic Order rules which should, amongst other things…

- make it much easier to implement ‘Try then Modify’ projects, through ETROs

- enable councils to more easily make successful experimental schemes permanent, by allowing permanence through an ETRO without then having to undergo a further full TRO process, with its repeat consultation.

The rules in England are much more fit for purpose, and these changes will move Scotland closer to England’s approach. However, there remain some aspects (such as the maximum length of an ETRO, or the scrapping of Redetermination Orders) which require changes in legislation rather than just in regulations; Spokes has urged that these are included in the next Transport Bill.

The traffic reduction challenge

In December 2020, as part of its Climate Change Plan Update [3.3.19] the Scottish Government adopted a target to reduce car-km 20% by 2030. The target was reaffirmed in the Programme for Government [PfG, page 98]. Given that motor traffic is rising, this is an exceptionally ambitious target – it therefore requires exceptionally ambitious policies for its success.

If achieved there would be major benefits to many policy areas, not least active travel. Streets in towns and cities would become less noisy, polluted and congested, making it more pleasant and safer to walk, wheel or cycle. A trend of falling car use and rising active travel /public transport would change public expectations of how and where we get around. Motorised use of road space would fall, as hopefully would complaints about congestion by those who still drive, thus making roadspace reallocation easier both politically and practically.

At the same time, inter-urban traffic would fall, reducing the demands for costly and climate-busting road building, boosting rail use and encouraging more local lifestyles.

.

The result in cities

The PfG states that we “must move beyond rhetoric and target setting to demonstrate the ambition the world needs.” Despite that, right from the announcement of the 20% target, we have doubted [section 2(b) in this submission] that the Scottish Government has understood the determination that will be needed to achieve it, and will be prepared to take the steps necessary. There are many reasons for our concern…

The example of previous targets

In 2010 the Scottish Government set a target (not just a ‘vision’) that 10% of all trips should be by bike by 2020. Ministers (even the First Minister) repeatedly highlighted and lauded the target as if it was grounded in reality, even when, with only 2 or 3 years remaining, the actual numbers had hardly changed. Ministers appeared throughout to believe that carrots alone would do the trick – and even the carrots, most of the time, were miserable wizened specimens offering no hope of nationwide change.

Traffic levels are rising

During 2021, since the target was announced, traffic has returned to, and in some cases already exceeded, pre-pandemic levels. Whilst some former car-commuters now work from home, many former bus or rail users have changed to car, suggesting a possible further rise if more people return to physical workplaces. And in 2019, prior to the pandemic, the Scottish Government was itself predicting that car trips would rise by 25% by 2037, and miles driven by 37%.

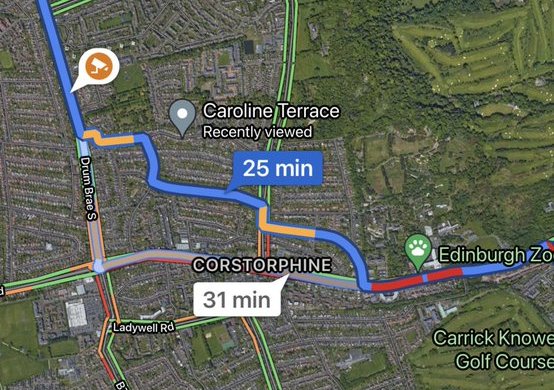

Moreover, whilst we might hope that the traffic reduction target would particularly benefit residential areas, the challenge there is even greater, with satnavs, googlemaps etc causing traffic to rise faster in local neighbourhoods than on main roads.

Delay in getting started

We were promised a ‘routemap’ by the end of 2021 as to how the target will be met. A routemap is welcome, absolutely vital, and something which was never done for the above cycle use target despite repeated urging from ourselves and others.

Unfortunately, the traffic-reduction routemap was put off from end 2020 to end 2021 on the grounds that we had to see how traffic settled down post-pandemic; and now there is talk of waiting till 2022. The delay allowed traffic to return and grow post-pandemic, rather than attempting to capture some of the benefits. Moreover the implicit message to the public is to get back to ‘normal’ rather than a message that car travel must be constrained.

Thus one of the 10 years to 2030 has already been wasted, traffic has risen, and public expectations of growing car use not addressed in the slightest. Furthermore, the routemap is to provide ‘options’ for action – which suggests further delay before difficult actions are attempted, albeit some of the uncontroversial ‘carrot’ actions (such as more AT cash) are now underway.

Carrots and sticks

We fear that the routemap will rely too heavily on carrots, although they, too, are vital. For example, the PfG says, “our investment in transport decarbonisation and active travel, will help drive forward our commitment to reduce the use of cars”. This recent letter takes a similar approach. The PfG, however, does also promise “an analysis of demand management options” – we wait to see what they are and, more tellingly, what Ministers are willing to adopt.

Chris Stark, CEO of the UK Climate Change Committee, which provides official advice to the UK and Scottish Governments, has already told MSPs that the target is a really tough one but that the Scottish Government’s transport proposals “are mainly carrots“ – and that reaching the target “will not happen unless there is a combination of carrots and sticks.”

Examples of the demand management measures which need to be considered by the Scottish Government are…

- Road pricing and/or congestion charging – indeed, according to Scottish transport expert Prof Iain Docherty, speaking at a meeting of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, some form of road user charging is probably essential if the target is to be met

- [Note that whilst increasing fuel duty is potentially an important lever, it is a UK decision, and its importance will decline with the transition away from fossil vehicles, making road user charging even more important]

- Widening the scope of the Workplace Parking Levy to a Premises Levy (‘PNR,’ private non-residential) to include charging out-of-town (and in-town) superstores, leisure centres, etc, for the number of customer car spaces, not just staff spaces

- Onstreet parking management rules, including removing some of the exemptions to the Pavement Parking law

- Incentivising councils to adopt demand management policies such as premises levies, parking management, congestion charging, motor-free town centres, roadspace reallocation, closure of rat-runs and car-dominated shopping streets as part of LTNs, LEZs, etc.

Road capacity expansion

Astonishingly, given both the climate emergency and the fact of a Green/SNP agreement, the PfG [p99] continues existing road building programmes, including the hugely costly dualling of the A9 and the A96, although the latter is slowed down somewhat by a ‘review.’ More locally, the £120m Sheriffhall flyover/roundabout remains on track for construction; and objections from Spokes and others to the M9 Winchburgh junction have just been dismissed by the government without even holding a public enquiry.

A recent Transform Scotland report, Roads to Ruin, finds that Scottish Ministers intend to nearly double their spending on new roads over the next decade.

Not only does this give the public an implicit message which contradicts the traffic reduction target, but in concrete terms it will mean increased traffic on these roads, making the target harder to achieve and leading to further impacts on the towns and cities connected by the expanded roads. The PfG does have a welcome commitment to not “normally” set up further new roads projects – but the length of time needed to set up new projects means that only those currently planned would in any case be likely to begin construction during the course of this parliament.

What you can do

If you are pleased and/or concerned by aspects of the above, please tell your MSPs and ask them to follow up and report back on the points that concern you. Send us any useful replies.

Find your MSPs here … www.parliament.scot/msps/current-and-previous-msps

Points you might raise…

- Happiness about the major boost to AT cash, but seeking assurance that the increase will be phased in starting with a substantial rise in the next budget (for financial year 2022/23) rather than leaving all or most of the rise until 2024/25

- Happiness about the traffic reduction target, but concern that government is doing far too little to restrain traffic growth, let alone reduce it. ‘Carrots’ such as more AT cash are essential and are welcomed but are far from sufficient.

Please also retweet our tweet of this article.